Grand opera in four acts by Giuseppe Verdi. Plot by Mariette Bey. Written in French prose by Camille du Locle. Translated into Italian verse by Antonio Ghislanzoni.

Produced in Cairo, Egypt, December 24, 1871; La Scala, Milan under the composers direction, February 8, 1872; Théâtre Italien, Paris, April 22, 1876; Covent Garden, London, June 22, 1876, Academy of Music, New York, November 26, 1873; Grand Opera, Paris, March 22, 1880, Metropolitan Opéra House, with Caruso, 1904.

AIDA, an Ethiopian slave Soprano

AMNERIS, daughter of the King of Egypt . Contralto

AMONASRO, King of Ethiopia, father of Aida . Baritone

RHADAMES, captain of the Guard . Tenor

RAMPHIS, High Priest . Bass

KING OF EGYPT Bass

MESSENGER . Tenor

Priest, soldiers, Ethiopian slaves, prisoners, Egyptians, etc.

Time: Epoch of the Pharoahs.

Place: Memphis and Thebes, Ancient Egypt.

"Aida" was commissioned by Ismail Pacha, Khedive of Egypt, for the Italian Theatre in Cairo, which opened in November, 1869. The opera was produced there December 24, 1871; not at the opening of the house, as sometimes is erroneously stated. Its success was sensational.

Equally enthusiastic was its reception when brought out at La Scala, Milan, February 7, 1872, under the direction of Verdi himself, who was recalled thirty-two times and presented with an ivory baton and diamond star with the name of Aida in rubies and his own in other precious stones.

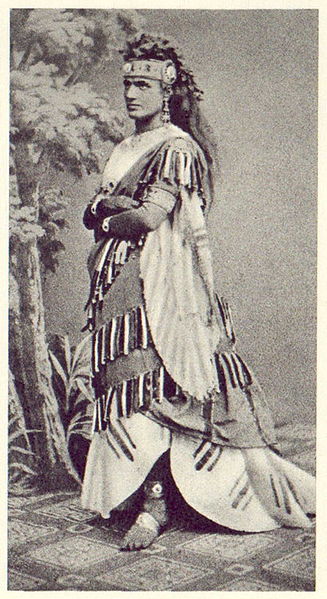

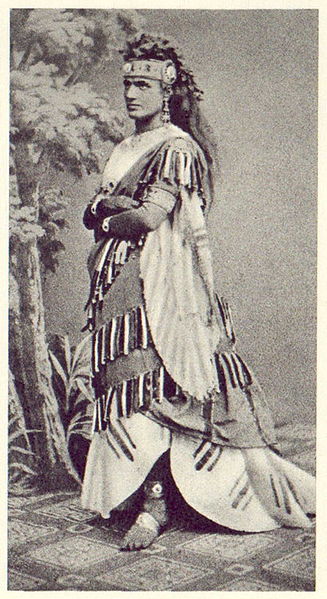

Teresa Stolz (soprano) as the title role of Aida, Parma, 1872

It is an interesting fact that "Aida" reached New York before it did any of the great European opera houses save La Scala. It was produced at the Academy of Music under the direction of Max Strakosch, November 26, 1873. I am glad to have heard that performance and several other performances of it that season. For the artists who appeared in it gave a representation that for brilliancy has not been surpassed if, indeed, it has been equalled. In support of this statement it is only necessary to say that Italo Campanini was Rhadames, Victor Maurel Amonasro, and Annie Louise Cary Amneris. No greater artists have appeared in these roles in this country. Mlle. Torriani, the Aida, while not so disntiguished, was entirely adequate. Nanneti as Ramphis, the high priest, Scolara as the King, and Boy as the Messenger, completed the cast.

I recall some of he early comment on the opera. It was said to be Wagnerian. In point of fact "Aida" is Wagnerian only as compared with Verdis earlier operas. Compared with Wagner himself, it is Verdian -- purely Italian. It was said that the fine melody for the trumpets on the stage in the pageant scene was plagiarized from a theme in the Coronation March of Meyerbeers "Prophète." Slightly reminiscent the passage is, and, of course, stylistically the entire scene is on Meyerbeerian lines; but these resemblances no longer are of importance.

Paris failed to hear "Aida" until April, 1876, and then at the Théâtre Italien, instead of at the Grand Opéra, where it was not heard until March, 1880, when Maurel was the Amonasro and Edouard de Reszke, later a favourite basso at the Metropolitan Opera House, the King. In 1855 Verdis opera, "Les Vêpres Siciliennes" (The Sicilian Vespers) had been produced at the Grand Opéra and occurrences at the rehearsals had greatly angered the composer. The orchestra clearly showed a disinclination to follow the composers minute directions regarding the manner in which he wished his work interpreted. When, after a conversation with the chef dorchestre, the only result was plainly an attempt to annoy him, he put on his hat, left the theatre, and did not return. In 1867 his "Don Carlos" met only with a succès destime at the Opéra. He had not forgotten these circumstances, when the Opéra wanted to give "Aida." He withheld permission until 1880. But when at last this was given, he assisted at the production, and the public authorities vied in atoning for the slights put upon him so many years before. The President of France gave a banquet in his honour and he was created a Grand Officer of the National Order of the Legion of Honour.

When the Khedive asked Verdi to compose a new opera especially for the new opera house at Cairo, and inquired what he composers terms would be, Verdi demanded $20,000. This was agreed upon and he was then given the subject he was to treat, "Aida," which had been suggested to the Khedive by Mariette Bey, the great French Egyptologist. The composer received the rough draft of the story. From this Camille du Locle, a former director of the Opéra Comique, who happened to be visiting Verdi at Busseto, wrote a libretto in French prose, "scene by scene, sentence by sentence," as he has said, adding that the composer showed the liveliest interest in the work and himself suggested the double scene in the finale of the opera. The French prose libretto was translated into Italian verse by Antonio Ghislanzoni, who wrote more than sixty opera librettos, "Aida" being the most famous. Mariette Bey brought his archeological knowledge to bear upon the production. "He revived Egyptian life of the time of the Pharaohs; he rebuilt ancient Thebes, Memphis, the Temple of Phtah; he designed the costumes and arranged the scenery. And under these exceptional circumstances, Verdis new opera was produced."

Verdis score was ready a year before the work had its première. The production was delayed by force of circumstances. Scenery and costumes were made by French artists. Before these accessories could be shipped to Cairo, the Franco-Prussian war broke out. They could not be gotten out of Paris. Their delivery was delayed accordingly.

Does the score of "Aida" owe any of its charm, passion, and dramatic stress to the opportunity thus afforded Verdi of going over it and carefully revising it, after he had considered it finished? Quite possibly. For me know that he made changes, eliminating, for instance, a chorus in the style Palestrina, which he did not consider suitable to the priesthood of Isis. Even this one change resulted in condensation, a valuable quality, and in leaving the exotic music of the temple scene entirely free to exert to the full its fascination of local colour and atmosphere.

The story is unfolded in four acts and seven scenes.

Act I. Scene I. After a very brief prelude, the curtain rises on a hall in the Kings palace in Memphis. Through a high gateway at the back are seen the temples and palaces of Memphis and the pyramids.

It had been supposed that, after the invasion of Ethiopia by the Egyptians, the Ethiopians would be a long time in recovering from their defeat. But Amonasro, their king, has swiftly rallied the remnants of his defeated army gathered new levies to his standard, and crossed the frontier -- all this with such extraordinary rapidity that the first news of it has reached the Egyptian court in Memphis through a messenger hot-foot from Thebes with the startling word that the sacred city itself is threatened.

While the priests are sacrificing to Isis in order to learn from the goddess whom she advises them to choose as leader of the Egyptian forces, Rhadames, a young warrior, indulges in the hope that he may be the choice. To this hope he joins the further one that, returning victorious, he may ask the hand in marriage of Aida, an Ethiopian slave of the Egyptian Kings daughter, Amneris. To these aspirations he gives expression in the romance, "Celeste Aida" (Radiant Aida).

It ends effectively with the following phrase: