This study assesses the differences between Islamic and conventional bank’s productivity. Earlier studies on bank productivity focused on conventional banks, but few have been done on Islamic banks. Therefore, the present study attempts to close the gap in the literature by investigating the productivity of Islamic and conventional banks in the context of the Middle East, Southeast Asia and South Asia regions. The sample is comprised of 385 banks (66 Islamic banks and 319 conventional banks) from 18 countries with data observations from 2008 to 2017. Panel data techniques with DEA-based MPI will be employed to investigate the impact of selected important factor and bank productivity as indicated by total factor productivity changes (TFPCH). Based on the results, Islamic banks are more productive than conventional banks and the results from t test are further confirmed by the results from nonparametric tests. These results are attributed to the progress in EFFCH. However, the mean difference between Islamic and conventional banks TFPCH is not statistically significant in all regions. The main benefit is that this work will hopefully provide additional insight and complement the existing studies on bank productivity of Islamic and conventional banks that are important to the banks, regulations, investors and researchers.

Nowadays, the banking industry continues to grow, at least, until another form of banking becomes available, and Islamic banking begins to gain further attention from Islamic and contemporary economists. Islamic finance is important for Muslims who require financial instruments that follow the Islamic legal code called Shariah [50]. Moreover, Islamic banks also have the potential to reduce risks endemic to financial transaction which have implication for economic growth [28].

The inception of Islamic banking began more than 30 years ago, and since this time, the aggregate of banks offering financial services has significantly grown to over 300 banks nowadays in over 75 countries from only one bank in 1975 [24]. Islamic finance is important for Muslims who require financial instruments that follow the Islamic legal code called Shariah [50]. Also, as the need for Shariah-compliant financial products and services increases, this sector will continue to rapidly grow in Muslim and non-Muslim market segments [13]. Referencing Table 1, it can be seen that within 9 years between 2009 and 2018, the total Shariah compliance assets significantly increased. Iran, Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait remain the primary markets for Islamic financial banking based on total Shariah compliance assets. Notably, South Asia and Southeast Asia countries, including the Middle East, dominate Islamic financing from a global perspective [4]. Therefore, taking these findings into account, it is important to comprehend the productivity and nature of both conventional and Islamic banking in these countries.

Here, MPI measures the productivity change from period t to t + 1, which reflects to a reference period technology. Thus, the MPI in relation to technology in period t is:

$$M_<0>^ = \frac^ \left( ,y^ > \right)>>^ \left(Corresponding output based MPI concerning technology in period t + 1 is:

$$M_<0>^ = \frac^ \left(Given it is complicated in choosing among period t and t + 1 as a benchmark period, an output-based MPI is defined as the geometric mean of Eqs. (1) and (2), [23]:

Accordingly, this can be broken down into efficiency change \(\left( >^ > \right)\) as well as technological change ( \(>^ )\) . As proposed by Fare et al. [23], an equivalent way of writing the MPI index is given below:

where M represents the level of productivity change as measured by a shift in frontier measured at years’ t and t + 1 in which most of the recent production point \(\left( , y^ > \right)\) correspond to the previous production point \((x^ , y^ )\) . However, when M > 1 it says that period (t + 1) productivity is higher compared to period t productivity. Although when M < 1, it says (t + 1) productivity is less compared to period t productivity which says that productivity regress and M = 1.000 correspond to inaction (no TFP change). Lastly, output distance functions are represented by D’s. The interrelation among the MPI and its two sub-indices can be shown as:

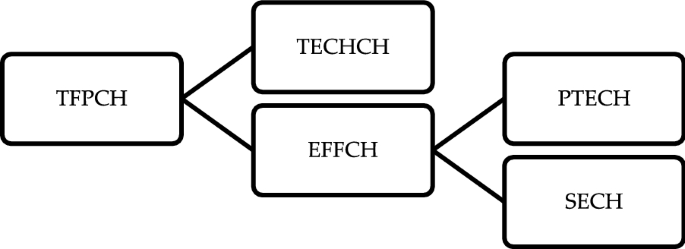

$$M_<0>^ = >\,> \times >\,>$$ $$>\,> = \frac^ \left(Therefore, to summarise the analysis of the first stage the TFPCH of banks were determined by employing output-based MPI. Next, VRS technology was used to measure TFPCH ( \(M_^ )\) relative to efficiency change (EFFCH) and technical change (TECHCH) as given in Eq. (5). Moreover, as proposed by Fare et al. [23], efficiency change (EFFCH) was then broken down further into the element of pure technical change (PTECH) which was determined based on the VRS technology. Accordingly, this was part of the scale efficiency change (SECH) employed to capture the variance among the constant returns to scale (CRS) and variable returns to scale (VRS) technologies as shown in Eq. (8).

The scores representing efficiency were constrained in order to remain amid zero and one and the year 2007 was used as the reference year. The MPI and its constituent parts started with a value of 1.000. Therefore, an efficiency value less (higher) than one for a bank in the following years meant that it was performing below (above) the frontier. Also, the value representing efficiency showed the radial distance from the estimated production frontier to the decision-making unit (DMU) being under consideration.

In order to study productivity, data envelopment analysis (DEA) is employed in this study as a primary tool because it is widely used and still relevant for measuring the productivity given it has been proved to be sustained over time for 40 years with more than a thousand papers published in a year [22].

Accordingly, the intermediation approach was adopted in this study in classifying the input and output of banks, as supported in many studies [12]. This approach has been widely adopted as the initial stage of DEA, given the significant part that banks enact in providing financial intermediation.

In this study, the selection of inputs and outputs was steered by the process as depicted in several studies [3, 19, 39, 55]. All variables employed in the nonparametric DEA were based on the MPI model as part of the initial stage of analysis, as depicted in Table 3.

Table 5 shows the geometric mean scores of the total factor productivity change (TFPCH) and its component, which is the Technical Change (TECHCH) and Efficiency Change (EFFCH) that can be decomposed into Pure Technical Efficiency Change (PTECH) and Scale Efficiency Change (SECH) for all banks (Panel A), conventional banks (Panel B) and IBs (Panel C). This analysis helps to understand the performance of the banks for each year.

Referencing Panel A in Table 5, it can be seen that all banks have, on average, exhibited a lower TFPCH regress of −15.2% (0.848). The results show that all banks exhibited TFPCH regress of −35.9% (0.641) in 2017. During the period of study, the −15.2% (0.848) regress in TFPCH of all banks could be attributed mainly to the −13.4% (0.866) decrease in TECHCH, as the EFFCH seems to have a decrease in the rate of −2.1% (0.979). The decomposition of the EFFCH index consists of PTECH and SECH components indicating that the reason for the decrease in all banks EFFCH was mainly attributed to PTECH rather than SECH. Therefore, considering these findings, all banks are less efficient in the management of cost control, even though they have been operating at the optimal scale of operations.

Panel B of Table 5 depicts the results for conventional banks. As can be seen in the table, the conventional banks’ average exhibited a TFPCH regress of −14.7% (0.853). The results indicate 2017 represents a TFPCH regress of −35.2% (0.648) for conventional banks. The decomposition of the TFPCH index into its TECHCH and EFFCH components reported that the regress in conventional banks’ TFPCH was solely attributed to a −12.1% (0.879) decrease in TECHCH, as the EFFCH decreased at a rate of −3.0% (0.970). The decomposition of the EFFCH index into its PTECH and SECH components indicates that the dominant sources that regress in conventional banks’ EFFCH were mainly managerially rather than of an operational scale.

Similarly, Panel C of Table 5 shows the MPI average results of Islamic banks. The empirical findings seem to suggest that the Islamic banks’ TFPCH decreased by −11.2% (0.888) higher compared to their conventional banks’ counterparts. The results show that for 2017 the TFPCH has a regress of 39.3% (0.607) and progress of 36.1% (1.361) in 2016 for Islamic banks. It can also be seen that within the period of study, the −11.2% (0.888) regress in TFPCH of all banks could be attributed to the −11.0% (0.890) decrease in TECHCH, as the EFFCH seems to have a decline in the rate of −0.2% (0.998). The decomposition of the EFFCH index into its PTECH and SECH components indicates that the decrease in EFFCH was mainly attributed to managerial factors rather than the scale.

Therefore, in summarising the findings, the TFPCH regress in conventional banks and Islamic banks mainly result from technological regression (TECHCH). Overall, the empirical findings indicate that the conventional banks and Islamic banks are operating at the optimal scale of operations but are less efficient in the management of cost control.

In order to control for possible outliers or extreme observations, Table 6 (see “Appendix”) reports the trend in the number and percentage of all banks that experienced productivity progress or regress during the period of study. Referencing Panel A in Table 6, in 2008, only 114 (34.44%) of all banks experienced productivity growth and then increased substantially reaching 198 (55.62%) banks in 2013. However, the number declined to 137 (37.64%) banks in 2017. The result also shows that the number of banks that experienced technological progress increased from 77 (23.26%) banks during 2008 to 196 (55.06%) in 2013 but drastically declined to 81 (22.25%) banks in 2017, Though the number of banks experienced technological regress declined from 228 (68.88%) banks in 2008 to 159 (44.66%) banks in 2013 but before radically increasing to 281 (77.20%) in 2017.

Panel B of Table 6 presents the trend in the number and percentage of conventional banks that experienced productivity progress or regressed between 2008 and 2017. The results suggest that the number of conventional banks experienced productivity progress increased from 92 (31.83%) banks in 2008 to 165 (53.92%) in 2014. However, the number of conventional banks that experienced productivity progress decreased gradually to 114 (37.75%) banks in 2017. Similarly, conventional banks exhibit technological regress decreasing from 200 (69.20%) banks in 2008 to 132 (45.05%) banks in 2013 and before rising to 237 (78.48%) in 2017.

Furthermore, Panel C of Table 6 presents the trend in the number and percentage of Islamic banks that experienced productivity progress or regressed between 2008 and 2017. In 2008, only 22 (52.38%) of Islamic banks experienced productivity growth, which increased substantially to 36 (57.14%) banks in 2013. However, the number declined to 23 (37.10%) banks in 2017. Likewise, Islamic banks which exhibited a technological progress rise from 10 (23.81%) banks in 2008 to 36 (57.14%) in 2013, reduced to 18 (29.03%) banks in 2017. Further, Islamic banks that exhibited technological regress inclined from 28 (66.67%) in 2008 to 50 (78.13%) in 2014 with the number marginally declining to 44 (70.97%) in 2017.

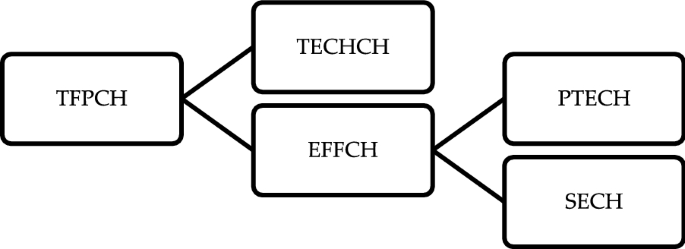

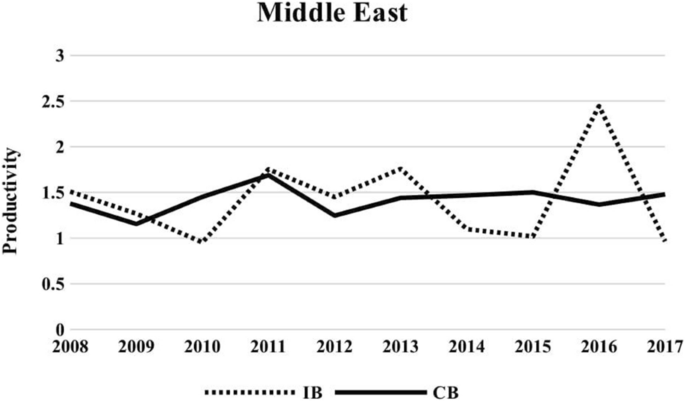

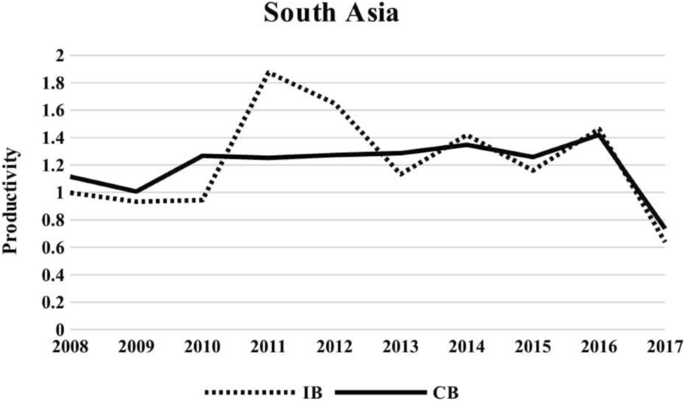

Observing in more detail in the ME region, as reflected in Fig. 2, the productivity indices of Islamic banks progressed in 2016 with 2.445 productivity indices and then regressed in 2010 (0.953). Furthermore, Fig. 3 reveals that productivity indices for both banks in the SEA region follow an inconsistent trend between 2008 and 2017, with productivity indices for Islamic banks peaking in 2008 (2.150) and in 2013 (1.815) staying relatively stable after that. While the Islamic banks reach their peak at 1.875 in 2011 in the SA region as reflected in Fig. 4, before slowly declining in the following year. Islamic banks and conventional banks in SA are rated as having the lowest productivity indices of 0.638 and 0.736 in 2017, whereas the productivity of Islamic banks in the ME and SEA was lower in 2010, at 0.953 and 0.967 productivity indices, respectively. On the other hand, ME conventional banks had the lowest productivity indices at 1.155 in 2009, while conventional banks in SEA had the lowest productivity indices of 1.075 in 2008.

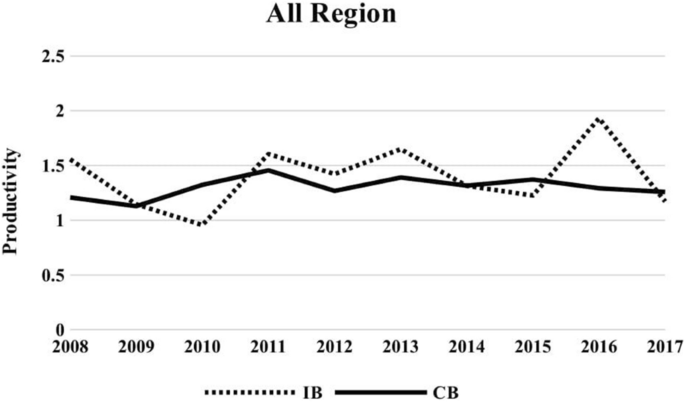

Figure 5 shows the trend related to the productivity of Islamic and conventional banks in all regions between 2008 and 2017. As seen in Fig. 5, the productivity of Islamic banks outperforms conventional banks in most years following the GFC in 2008 and 2009. On average, both Islamic banks and conventional banks have productivity indices above 1.00, indicating that the banks’ have experienced progress in their productivity compared to the prior year. We can also see productivity indices for both banks show the unevenness of the trend between 2008 and 2017, where productivity indices for Islamic banks peaked in 2008 (1.556) and 2011 (1.604), before gradually decreasing from 2013 (1.649) to 2015 (1.226) and reaching a peak in 2016 (1.931). However, the productivity of conventional banks from all regions remains relatively stable in the lowest level range of 1.129 in 2009 to the highest level of 1.455 in 2011.

The reason of this condition is Muslim population is increasing especially in Southeast Asian region which made substantial popularity in the ethical character and financial stability in Islamic finance product and services as an alternative to conventional financing mechanisms [41]. Moreover, the issuance of global Sukuk in 2012 has been growing in popularity and utilised by both corporate sector and sovereigns for raising fund in Southeast Asian country, in particular, Malaysia, followed by Indonesia to promote Shariah-based financial product that enabling these regions to dominate over 70 per cent of the world’s Sukuk issuances [41]. Furthermore, South Asia has made investment for their infrastructure development which is one of the major obstacles to the economic growth in year 2016 [8]. Sukuk played an important role in financing the infrastructure projects in South Asia region [41].

To conclude, Fig. 5 shows the overall empirical mean productivity level in all regions indicating that Islamic banks have a higher overall productivity level compared to conventional banks [1.931 (2016) vs. 1.455 (2011)]. This suggests that the Islamic banks are more productive than conventional banks in managing their operations. The level of productivity in Islamic banks in all three regions (ME, SEA and SA) [2.445 (2016), 2.15 (2008), 1.875 (2011)], respectively, is higher than in conventional banks [1.689 (2011), 1.306 (2011), 1.348 (2014)].

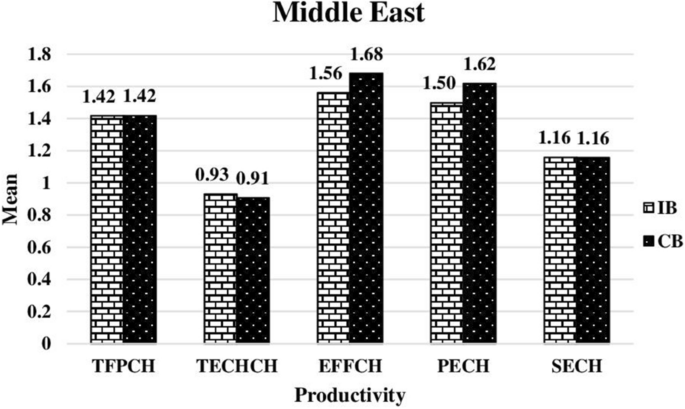

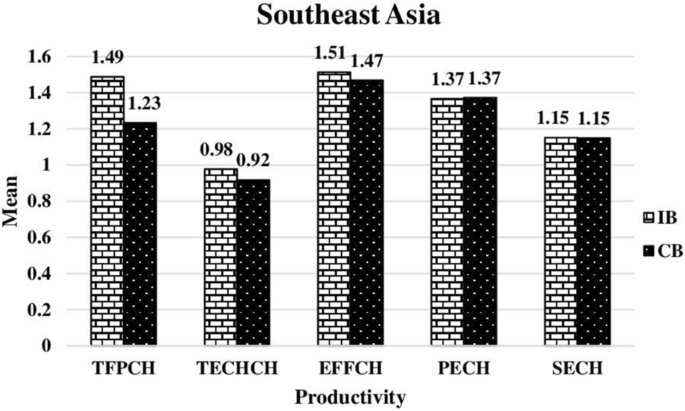

Figure 6 represents the productivity component of Islamic and conventional banks in ME countries between 2008 and 2017. The TFPCH are almost similar for both types of banks in the ME; Islamic banks (1.417) and conventional banks (1.418). The TFPCH progress in both banks results from higher EFFCH, which means there is an improvement in the management of the banks. When looking at the decomposition of the EFFCH, both banks have progressed in PECH. Figure 7 shows the productivity component of Islamic and conventional banks in SEA countries between 2008 and 2017. Here, overall, Islamic banks have higher TFPCH (1.488 vs. 1.233), TECHCH (0.977 vs. 0.918), EFFCH (1.513 vs. 1.469) and SECH (1.152 vs. 1.149), while conventional banks have slightly higher PECH (1.372 vs. 1.367) than Islamic banks. The TFPCH in both banks results from the EFFCH. When considering at the decomposition of EFFCH, both banks have progressed in PECH.

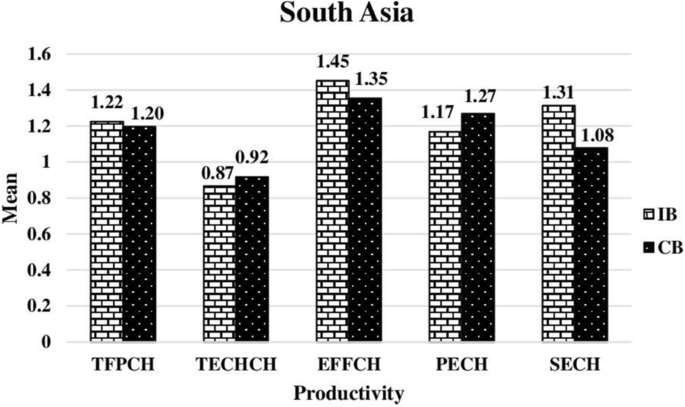

Figure 8 confirms the productivity component of Islamic and conventional banks in SA countries between 2008 and 2017. Overall, Islamic banks have higher TFPCH (1.488 vs. 1233), EFFCH (1.513 vs. 1.469) and SECH (1.152 vs. 1.149). While conventional banks are higher in TECHCH (0.977 vs. 0.918) and PECH (1.367 vs. 1.372) than Islamic banks. The TFPCH in both Islamic and conventional banks results from EFFCH, same as for other regions. The decomposition of EFFCH shows that both banks have progressed in SECH.

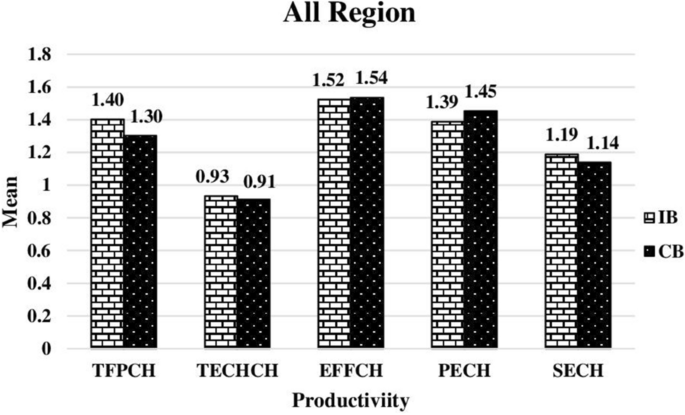

To conclude, Fig. 9 reveals the overall empirical mean productivity level in all regions indicating that Islamic banks have a higher overall productivity level than conventional banks (1.402 vs. 1.302]. This suggests that Islamic banks are more productive than conventional banks in handling their respective operations. The level of productivity in Islamic banks in all three regions (ME, SEA and SA) [1.417, 1.488, 1.224] is higher than in conventional banks [1.418, 1.233, 1.196], respectively.

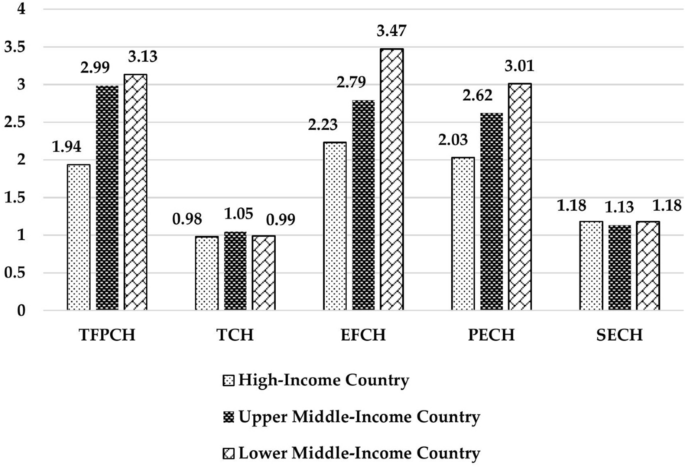

Figure 10 represents TFPCH of Islamic banks in different income groups which are high-income, upper middle-income and lower middle-income countries from year 2008 to 2017. Overall, high-income countries have lowest TFPCH, TECHCH, EFFCH and PECH. While lower middle-income countries have higher TFPCH, EFFCH, PECH and SECH. The upper middle-income countries have slightly higher TECHCH than high-income countries and lower middle-income countries.

The reason of this condition can be related to the increasing number of Islamic banks in the upper middle-income countries and lower middle-income countries such as Malaysia, Indonesia, Pakistan and Bangladesh. High Muslim population with their income levels has a positive effect on the Islamic banking system development [16]. As the number of Islamic banks in these income groups is increasing especially in Malaysia and Indonesia, it creates a highly competitive market among them. According to Abedifar et al. [2], the coexistence of both banks in the market can motivate the banks to be more innovative and increase the efficiency of whole banking system by improving competition.

As we can see from Fig. 10, the TFPCH in all income group countries comes from the EFFCH and this means there is managerial change in the banks. According to Boukhatem and Moussa [16], countries that have adopted mixed legal system based on Common law and Islamic (Shariah) law enable them to be flexible in response to the shift in macroeconomic conditions has contributed to the Islamic banks development.

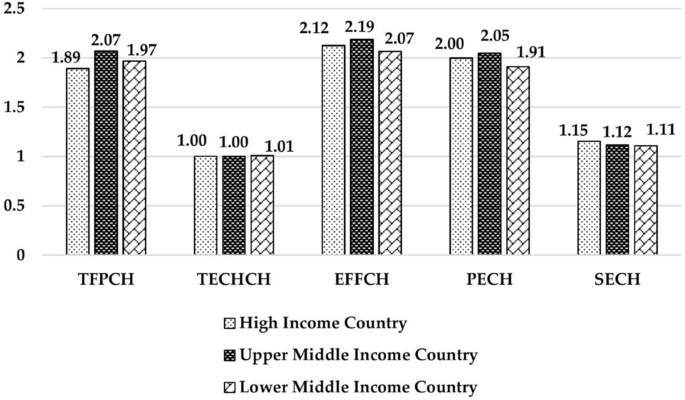

Figure 11 represents the TFPCH for conventional banks in different income groups from year 2008 to 2017. The upper middle-income countries have slightly higher TFPCH than high-income group countries and lower middle-income group countries. Most of the changes are come from the EFFCH due to managerial efficiency. This result is in line with the findings of Aluko and Ajayi [1]. They found that lower income countries tend to have more efficient banks than high-income countries. High-income countries have a larger size of banking industry and they face more competitive pressures that can lead to larger agency cost and higher overhead costs, subsequently leading to lower productivity in bank operation [25].

Table 7 (see “Appendix”) presents the significant difference between the productivity levels of Islamic and conventional banks in specific years and regions derived from the parametric (t test) and nonparametric (Mann–Whitney [Wilcoxon] and Kruskal–Wallis tests) tests. The empirical findings presented in Table 7 suggest that the Islamic banks are marginally more productive than conventional banks in all regions. However, the difference is only statistically significant during 2008 and 2016 (Panels A and I). On the other hand, Panels B, C, G, H and J in the t test suggest that the conventional banks have been relatively more productive than Islamic banks. However, the results are only statistically significant in Panel C. The results from nonparametric tests further confirm the t test results.

Whereas, for the ME region, the results imply that the TFPCH level for Islamic banks is more progressed than in conventional banks in six out of the 10 years under examination. The results are significant at a 5% level in Panel I. However, it can also be observed that conventional banks have higher TFPCH than Islamic banks in the ME region and are statistically significant in Panels C and J. Notwithstanding, Islamic banks have been relatively more progressed in terms of productivity compared to conventional banks in Panels A, E, F, H, I and J in the SEA region. However, only Panels A and I are statistically significant at 10% and 5%, respectively. Nevertheless, Panels D, E, G and I suggest that Islamic banks are more productive than conventional banks in the SA region but only statistically significant at 1% in Panel D. The results also suggest that conventional banks are more progressive than Islamic banks in SA the region in Panels A, B, C, F, H and J. However, the difference is insignificant.

When analysing the results further, the findings also show the component of the MPI, including the TECHCH, EFFCH and decomposition of EFFCH, namely PECH and SECH. Here, the findings show that Islamic are relatively more productive, attributed to higher TECHCH and statistically significant in Panels E, F and J. On the other hand, conventional banks are present more TECHCH and are statistically significant at Panel H. Likewise, the EFFCH in Islamic banks is higher in Panels D, E, H and I and lower in Panels A, B, C, F, G and J. When we look at the decomposition of EFFCH, Islamic banks are statistically significant to have been progressed in PECH, as reflected in Panels I and J. However, the Islamic banks only experienced SECH progress in Panel H and is statistically significant at the 5% level.

Panel K of Table 7c presents the results based on all years and regions. Based on the results, Islamic banks are more productive than conventional banks with a mean difference of (1.402 > 1.302 = 0.100). The results from the nonparametric tests further confirm the results from the t test. These results are attributed to the progress in TECHCH with a mean difference of (0.019) and statistically significant at 10% levels. The mean difference between Islamic and conventional banks TFPCH is not statistically significant in all regions, though.

The ME, SEA and SA regions also show that Islamic banks are more productive than conventional banks in Panel K of Table 7c. In the ME region, the productivity levels are similar for both types of banks (1.418 = 1.418); though, it is not significant at any level. The difference is only statistically significant in the SEA region with 5% levels. The productivity attributed to higher TECHCH is statistically significant at 1% levels. The results from the parametric t test are further confirmed through the nonparametric Mann–Whitney (Wilcoxon) and Kruskal–Wallis tests.

The results on the means for TFPCH in the Islamic and conventional banks in SA revealed that the TFPCH in the Islamic banks has a higher mean compared to conventional banks (1.224 > 1.196); however, it is not statistically significant. The progression in productivity for Islamic and conventional banks originates from the TECHCH and is significantly different at a 1% level (under the nonparametric test). Overall, the mean difference shows that Islamic banks are more productive than conventional banks in all regions, namely the ME, SEA and SA regions.

Therefore, in summary, it was revealed that Islamic banks tend to be more progressive compared to conventional banks but insignificantly different. This conclusion appears to be consistent with the results of earlier research that Islamic and conventional banks may not completely translate into visible distinctions. Given the benefit that conventional banks enjoy over the Islamic banks, where conventional banks have a very long history and expertise, their main income comes from interest, has very huge capital, spreads broadly and has much more advanced technology, the findings of this study are in favour of the later banking system. Beck et al. [11], for instance, point out that Islamic banks have produced products that emulate conventional banking products, replacing interest rate payments and discounting with fees and contingent payment arrangement. Likewise, Khan [40] concludes that there are considerable gaps between Islamic banking and finance principles and their real practice, but most of Islamic banking and finance remains technically indistinguishable from conventional banking. In addition, Bourkhis and Nabi [17] also point out that in Islamic bank, only 20% are committed to long-term and risk-sharing funding and argue that Islamic banks emulate conventional banks and diverge from their theoretical business model. The findings of Doumpos et al. [21], Hassan et al. [30], Bader et al. [9] and Mohamad et al. [47] are also in favour of this finding.

This study seeks to add to the literature on banks performance. As the Islamic banking growth is rapidly soaring, it is imperative to study their productivity. This paper aims to analyse total factor productivity change of Islamic and conventional banks covering 18 countries with dual-banking systems in the context of Middle East, Southeast Asia and South Asia regions. By using nonparametric DEA-based MPI method, the data are tested using parametric (t test) and nonparametric (Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis) tests. Although the theory suggests that there is distinctly difference between Islamic banks compared to conventional banks in the effect of various productivity determinants such the complexity, agency cost, level of maturity and development, empirical estimation suggests that there is no statistically significant difference between the total factor productivity (TFPCH) of the Islamic and conventional banks.

Further examination on the specific years for two banking types shows Islamic banks has exhibited a marginal productivity progress than conventional banks in nearly all the year. Moreover, this study also looked further into specific regions in the context of Middle East, Southeast Asia and South Asia regions. The findings suggest that Islamic banks are more productive than conventional banks in most of the years for all regions. Almost all the progression in productivity of Islamic and conventional banks are solely attributed to the increase in efficiency change (EFFCH). This signifies that both Islamic and conventional banks are efficient in their managerial.

Banks performance has attracted much concern in the banking and finance world. This study has provided important implication for policy makers and business practices. Therefore, determining the overall productivity level of Islamic banks can be a guidance to the policy makers to improve managerial performance, and investors and clients to make other decisions relating to investment and service quality. The progressive in productivity of the bank is expected to continuously improve the banks’ profitability by providing a high-quality service at a minimum cost. One key enable for such commitment would require banking and finance sectors to find the mechanism such as policy matter, workforce trainings and supports to soar up the productivity levels on the institutions. The findings in this study are in line with the existing literature on finance and development.

Furthermore, several limitations are inherent in this study, in which future researchers could explore. First, as this study examined the TFPCH of banks between 2008 and 2017, to achieve a consistent and comparative analysis, relatively little information was collected. As such, there were various aspects of productivity patterns that could not be discussed. Therefore, further research is needed in the future, considering a longer period of time, in order to explore the key determinants of productivity progress in the banking industry.

Secondly, this analysis may be further improved if the ratings of the financial institution are used as one of the factors to assess if higher-rated banks are better than lower-rated banks or vice versa. In addition, the regulatory regime of the various countries may be another consideration. There are well-developed regulations for Islamic banks in some countries, while others do not. Some factors that may be taken into consideration are that Basel III was introduced during the 2007–08 financial crisis, which could have influenced the risk-taking conduct of financial institutions.

Due to its limitations, this study provides the avenue and incentives to seek greater insight for a more deepened understanding and investigation on the productivity levels of two banking types. Future research may consider investigating the different bank production measurements such as production approach and revenue approach as this study is using intermediation approach in determining the specifications of bank’s input and output. Besides, the nonparametric frontier analysis can be combined with the parametric stochastic frontier analysis method to attain more robustness empirical evidence. This study, therefore, offers motivations for the institutions to formulate strategic choices to escalate the productivity level of the banks.

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.